by Rachel Cohen (28/8/23)

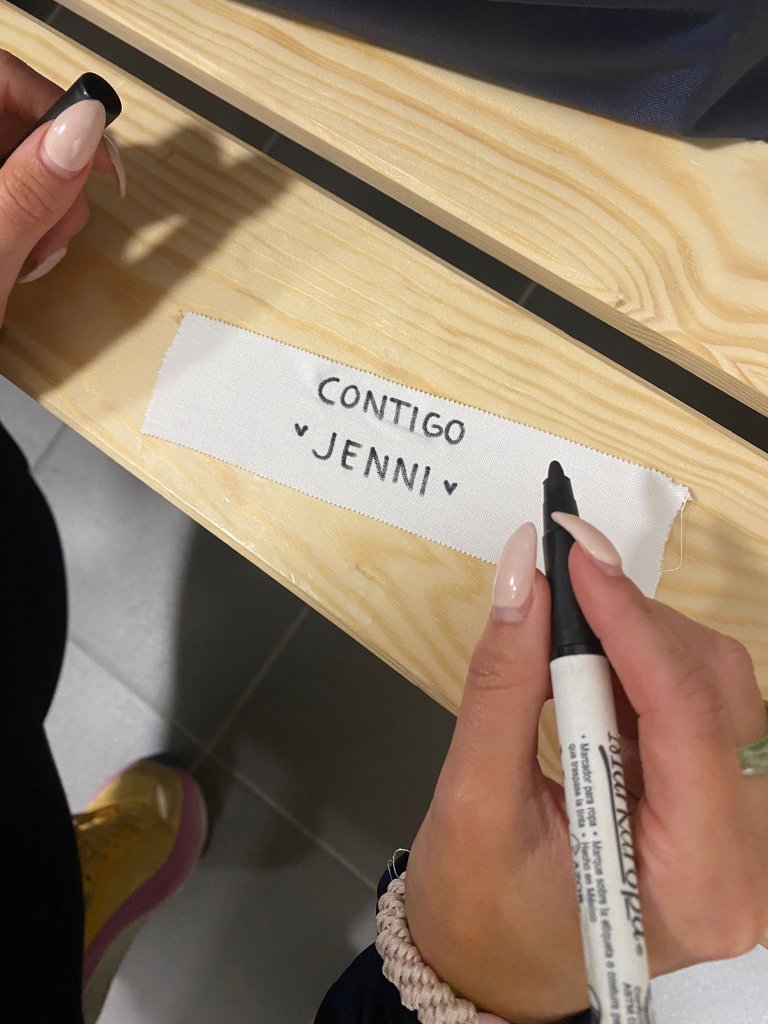

Above: Players from Atlético Madrid and AC Milan show their solidarity with Jenni Hermoso, a former Atléti player before their Women’s Cup match yesterday. Photo: Diego Souto.

If you’re like me you were a) obsessed with the World Cup and b) have spent much of the week since then alternately flabbergasted, horrified, and disgusted at the ways in which the Spanish Football Federation (RFEF) have destroyed any iota of credibility they had.

You may also have been inspired by the solidarity shown by players and non-playing women’s team staff in Spain and players and women’s football fans around the world. It has been a lot – to process, watch, listen to. It has also been revealing.

In case you have been paying less attention, this is about RFEF President, Luis Rubiales’ abuse of Spanish player Jenni Hermoso at the end of the World Cup Final. This abuse was first relayed on television to millions globally, then replayed endlessly on social media and news reports.

That means that the image of Rubiales holding Hermoso’s head against his as he kissed her on the mouth is now seared into everyone’s brains as are the various images of him repeatedly grasping at the bodies of other players, or grabbing and thrusting his own crutch in celebration while standing next to Spain’s monarch.

What we saw was a glimpse on the biggest stage of a leading figure in women’s football expressing his limitless entitlement, especially insofar as that extended to the bodies of female players under his employ.

He said afterwards that he believed that what happened was normal, not out of the ordinary. And we probably need to believe him on that at least – that this behaviour is normal for him. What was, however, new was those millions of eyes watching and calling him out on it. And that has resulted in a week in which Rubiales’ behaviour and the behaviour of those closest to him has remained in the spotlight. With that spotlight so much has been revealed – not just what happened at the Final, but also in the years leading up to that.

RFEF Modus Operandi Revealed

What has most stood out over last week is the ruthlessness of the RFEF, the organisation’s unwillingness to deviate from a course of action set by its leadership, to back their man, no matter what, and, as part of that, their shocking readiness to resort to what can only be described as manipulation, gaslighting and vindictive hostility.

- Manipulation: This was first seen during the flight back to Spain when repeated pressure was applied by Rubiales and Vilda, petitioning on Rubiales’ behalf, to Hermoso, her family and teammates, and to Spanish team captain (and presumed more ‘friendly’) Ivana Andrés. The objective was to persuade one of them to stand alongside Rubiales and legitimate his videoed denial that anything that untoward had occurred. Neither agreed. So instead, the RFEF sent a ‘statement’ on behalf of Jenni Hermoso that she did not see or agree to (see gaslighting, below). This meant that by the time the flight landed most of the media were confused about Hermoso’s position.

But these were not the only instances of manipulation and unacceptable pressure this week. On Saturday all members of the women’s team coaching staff, except Vilda, resigned en-mass, calling for a change of leadership. Their resignation letter revealed that female non-playing staff had been forced to attend Rubiales’ speech on Friday, to sit in the front row and to applaud in order to present a façade of women’s approval of the President’s aggressive denials and claims.

- Gaslighting: Here the RFEF’s statements are textbook, specifically designed to make us doubt what we know happened BECAUSE WE SAW IT WITH OUR EYES. After all, not only have we all seen the televised abuse but also widely circulated Instagram live video from the changing room immediately post-game in which Jenni Hermoso stated that she did not want what had happened. Then, on Friday, Hermoso released a statement via her union and agents in which she reiterated that she had not consented. In other words, in the immediate aftermath of the game Hermoso said that she did not give consent and five days later she doubled down, saying exactly the same. Moreover, given that time for reflection, in the Friday statement she was able to clearly name what had happened as abusive. Yet RFEF statements ignore all of that and instead parse the on-stage interaction into tiny moments, presenting stills, examining who was leaning into or away from whom as if this matters. While Rubiales went further in his Friday speech to RFEF, positing a little dialogue in which (conveniently) Hermoso gives explicit consent for a kiss while they are on the stage:

“I said, ‘Forget about the penalty, you’ve been fantastic, we wouldn’t have won the World Cup without you.’ She said: ‘You’re great.’ I said, ‘A kiss?’ and she said: ‘Yes.’”

When RFEF has claimed that their “evidence” “proves” that Rubiales must be believed and that Jenni Hermoso wanted what happened to happen they are engaging in the type of gaslighting and victim-blaming (‘she wanted it’) that is only too common in sexual abuse trials. To see it perpetrated by an organisation responsible for Spanish football and, as part of that, of player wellbeing is shocking. In none of this is there any recognition of power – and that as Casey Stoney so eloquently articulated it is always inappropriate for someone in a position of authority to initiate sexual contact with someone over whom they exercise power.

In other parts of their statement RFEF also implicitly question whether the statement released by Futpro (the players’ union) accurately quotes Hermoso. In doing this – and with zero irony – RFEF’s own untrustworthiness and falsification of Hermoso’s words is transformed into a reason to question other sources.

- Vindictive hostility: The RFEF and Rubiales have acted with hostility and aggression over and again. Starting with Rubiales himself, who in informal mode on a radio interview called those who were concerned about his action ‘idiots and stupid people’ and later in his non-resignation speech attacked ‘false feminists’ as propagating the suggestion that he acted abusively. They have made veiled, and not so veiled, legal threats against Hermoso and against any players who refuse to play for the national team – something that the entire World Cup squad and dozens of other Spanish players have pledged. We also see aggression in language that repeatedly and publicly states that Hermoso, who is employed by the RFEF and therefore owed a duty of care, ‘lies in all statements she makes’ (note: this language was removed but was on the RFEF official website for a few hours on Saturday).

Even in the immediate aftermath of the World Cup final, we saw triumphalism and hostility. Most obviously in RFEF’s social media which on full-time tweeted: ‘#Vildain’, a reference to the hashtag #Vildaout, used by supporters of Las 15. There are of course those that do argue that the win ‘validated’ Vilda’s stewardship. I disagree, but your position on this is irrelevant, the point is that a national federation used a world cup victory to get one over on their own team’s supporters. That is seriously petty.

A glimpse behind the curtain

What happened this week – the manipulation, hostility, and gaslighting used in defence of Rubiales – tells us a lot about how RFEF has been operating. And it helps make sense of the complaints of Las 15, the Spanish players who wrote a letter of complaint after last summer’s Euros in which they asked for improvements. It also makes sense of why some players, under pressure from their clubs and the federation (no doubt employing similar methods to those seen here), did not sign up to that letter.

The ways in which RFEF and Rubiales handled Las 15’s complaints looks all too familiar from this vantage point: instead of meeting and talking with the players and instead of looking for a solution they made public the players’ communication at the same time as they circulated an aggressive response branding the attempt to get change as “blackmail”, “unprecedented in the history of football” and that players must “admit their error and apologise” or face bans of up to five years. And then there is the grudge-holding visible in Vilda’s selection of just three of those players who came back, making themselves available for selection, bringing in only those most obviously necessary: Aitaina Bonmati, Mariona Caldentey and Ona Batlle (Bonmati and Batlle went on to start every game at the tournament and Caldentey started five of eight).

It makes sense that some players who experienced this, most notably Barcelona starters Mapi Leon, Sandra Panos, and Patri Guijarro, did not think anything was going to change and continued to make themselves unavailable for selection, sacrificing their chance to play at the World Cup.

But it also makes sense that other players gave up believing that any action they took would achieve more than the few improvements it had already wrought and that they ended up returning to a federation and coach that had not supported them, but which provided their only opportunity to play for their country. It was a poisoned choice. But we know that people return to those who abuse them. This is not their fault.

A Rotten Institution

What has happened in the aftermath of Rubiales’ assault, and what happened over the last years has revealed the institutional misogyny at the RFEF. It is not simply the acts perpetrated, or words spoken, by the President. But rather the complicity and disregard for players from him and from the organisation charged with managing Spanish football – men’s and women’s.

Those statements that have been made – backing Rubiales; pushing back on players – have been made in the name of the RFEF and come adorned with corporate branding. The legal teams employed pressure placed on employees, the falsely attributed words, coordination of institutional responses and push back against Las 15, was not the work of one man. This is not surprising.

There is plentiful evidence of Rubiales’ ties to people in positions of power and many have enabled and benefited from his tenure in the RFEF. One of those is Jorge Vilda, the coach Rubiales has backed throughout, who has (with his father behind him) been a big supporter of the President, and who for most of this week had Rubiales’ back, pressuring Hermoso’s family on the President’s behalf, clapping his speech. Until that is (perhaps sensing the winds of change) late on Saturday, long after players, coaches, politicians, and supporters around the world had spoken out, and only after the Spanish men’s coach did likewise, Vilda issued his own mildly worded critique.

If Rubiales’ actions have been facilitated by many others, suspending Rubiales (which has now happened, following FIFA bringing charges) or permanently parting company with him (hopefully around the corner) is essential but not enough.

We need wholesale change. That means new people, without ties to current leadership. It also means creating avenues for players to raise concerns and ensuring they are supported in doing this by their representatives.

It is worth remembering that while Spain has managed to make their problems very visible RFEF is not the only federation failing its players. Across the world we have seen players protesting about not being paid (Jamaica and South Africa), being underpaid (Canada and the UK), and about serious abuse. Most seriously, Zambia’s manager faces charges of demanding sex from players as quid pro quo for selection and against whom new allegations emerged during the World Cup.

#SeAcabó (It’s Over)

Women’s football deserves better.

Players deserve not to be abused. They deserve to work in an environment in which they are supported to play, not manipulated, gaslit, and threatened. After all, if Spain won the World Cup while dealing with all of this, it’s frightening to think what those players could do with a little bit of support.

Meanwhile, the actions of RFEF have laid bare the misogyny, manipulation, and abuse that women footballers suffer, but they have also provided glimpses of something hopeful. We have seen women footballers, coaches, and supporters in Spain and around the world coming together to organise, take action and fight back. And this time it’s not 15 but 81 Spanish women’s team players and they are not sending individual letters but are coordinating publicly and with their union. This time it will be harder to find replacement players or pressure them individually to concede.

And if this last week has shown us how viciously men in positions of power will fight to retain what they see as their entitlement, it has also shown that they may not be as invincible as they believe themselves to be.

Follow Impetus on social media – we’re @ImpetusFootball on Threads, Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook. DON’T MISS our brand new TikTok platform @ImpetusFootball too!